Abstract

The field of bioethics has always been refining and articulating moral frameworks. It is one to follow a pre-established moral system, such as the Hippocratic oath, or the four principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice; it is, however, another to decide which moral system to follow. The following paper would sketch out the different strands of thought that each has its own significance and issues in addressing real-life ethical dilemmas and making moral judgments. The approximate structure of the conflict between theories can be roughly presented as a disagreement of whether convergence or divergence at different ethical levels. Lastly, the methodology of phenomenology is briefly discussed as a possible ethical tool to alleviate the inefficiencies found in these different ethical frameworks. By elaborating on the structural basis of each ethical theory, this paper aims to clarify the discourse and to present the theoretical contributions and flaws of each framework.

Rossian Prima Facie Duty

Prima Facie Duty and Actual Duty

Prima facie duty, elaborated by W.D. Ross, is a classical moral framework theorizing the deontological values behind moral actions. Prima facie, translated from Latin “at first sight”, refers colloquially to judgments that we, “at the first impression”, consider to be correct unless for other reasons. In bioethics, we may understand an act to be a prima facie duty if “[such] act is a token of a type of act which would make it an actual duty if it were not also a token of another morally significant type of act” (Atwell, 1978). This other morally significant type of act can be understood as another prima facie duty. As this phrasing suggests, in any real life scenario, there exists multiple prima facie duties to be considered to determine what one’s actual duty in that specific scenario is.

Most acts don’t simply have only one feature that would conclude the act to be actually right or wrong, or in other terms, most actual duties do not arise from the consideration of a sole prima facie duty. In this manner the features or parts of an act cannot be actually right or wrong, though they may be prima facie right or wrong, but rather the totalization of all the features at hand, “total acts”, is to be judged in actual terms (Atwell, 1978). For example, from a morally intuitionistic standpoint, if I were faced with an ethical dilemma in which I have to lie in order to prevent a person from harm, most likely my actual duty is to lie, if it is given that the lie itself is relatively consequenceless. Here the balance of prima facie wrongness and prima facie rightness is reflected in the actual duty. If the lie itself is not without further implications, such as if it causes another person’s harm, the actual duty may differ, and in other cases it may be determined that the prima facie wrongness of the case outweighs the prima facie rightness. From here, one can formulate that, from a Rossian standpoint, “an action is morally obligatory [if and only if] its total prima facie rightness minus its total prima facie wrongness is greater than that of any of its alternatives (Olsen, 2014).”

Absolute Moral Principles or Not: Generalism vs. Particularism

While it is undeniable that Ross is a generalist when it comes to prima facie duties, that is, he recognizes prima facie duties as substantive true moral principles (Olsen, 2014), whether actual duties are particular or general is controversial. Olsen’s formulation of a morally obligatory action implies that there are absolute moral principles when it comes to making actual judgments. The archetypes of absolute (actual) duty generalism include classical theories such as utilitarianism and Kantianism. The former evaluates the moral obligation of an action based on the balance of pleasure/utility (Olsen, 2014) while the latter on the action’s adherence to the categorical imperative: for example, taking the principle of dignity to be the universal supreme formal principle in the categorical imperative by which everyone should follow and be the basis by which to judge conflicting contingent material principles (Heinrichs, 2010). Generalists (for actual duty) hold that there is an absolute actual duty derived from the permutations of relevant prima facie duties, each of which contributes a similar moral valence across different moral situations (Dabbagh, 2008; Olsen, 2014).

Particularists subscribe to the idea of holism, which states that a contributory feature/reason for an action does not necessarily contribute to another action in the same way, or even contribute to the justification of the action at all (Dabbagh, 2008; Olsen, 2014). The moral contributions of different factors are considered holistically, with the actual duty reflecting upon a contextual summation of all the contributory factors, without telling anything about the substantive moral value of any individual contributory factor; contribution varies from case to case (Dabbagh, 2008). It can be criticized, however, that by considering the holistic picture of the different factors at hand, one has already committed atomism, which sees each factor as having an intrinsic deontic value that stays consistent throughout different cases. Atomism supports generalism as it allows an absolute actual duty to be extracted from the atomic deontic valences of the morally relevant (usually prima facie) features. Particularism therefore utilizes the argument made by the generalists, but is itself unable to give a clear description of the moral details within its vague holistic account (Dabbagh, 2008).

Beauchamp and Childress’s Principlism

Deductivism and Inductivism

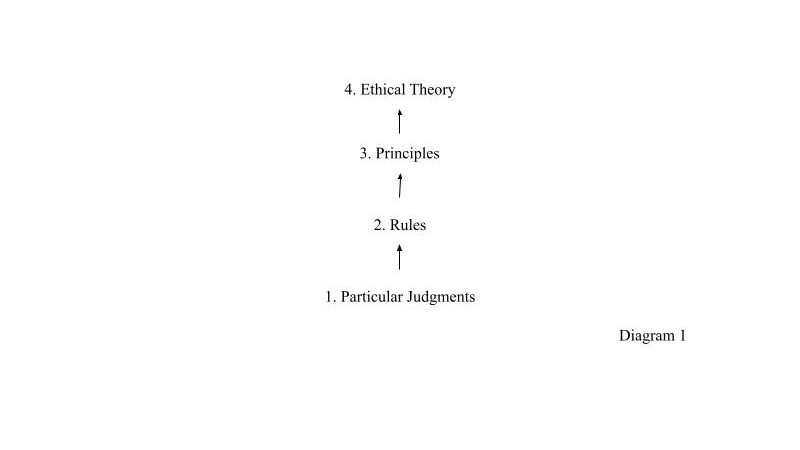

Deductivism, or the covering-precept model, deduces justified moral judgments from a higher level normative ethical framework (Beauchamp and Childress, 1994). As the following diagram depicts, the development of particular moral judgments depends on sets of pre-existing rules; these rules, in turn, were developed from principles that were derived from an overarching ethical theory. Each moral level is justified by its more general covering precept through deductive reasoning: principle x is a principle that is morally obligatory; rule y is established to be coherent with principle x; rule y is therefore morally obligatory by modus ponens (Beauchamp and Childress, 1994).

Deductivism suffers from its indeterminate generality and its inability to reflect the nonlinear nature of most situations where moral judgments need to be made. The issue in many cases mostly does not come down to a lack of consensus of a general ethical theory, but rather, a metaphysical account of the situation; even if everyone agrees that it is good not to kill, abortion still remains controversial due to the debate of when a fetus becomes life. Furthermore, it is never immediately obvious which covering precept would be applicable in any specific case and often multiple chains of deductive justifications can be made even when the facts of a given situation are agreed upon—this results in different moral judgments (Beauchamp and Childress, 1994). Lastly, deductivism generates infinite regress when it comes to justifying every level with a higher-level covering precept.

Inductivism, on the other hand, places emphasis on the ability of cases to affect principles and rules. Resolution of moral cases can reveal pre-existing social agreements, intuitions, and practices. The practice of casuistry, for instance, allows practitioners to determine appropriate moral judgments by past cases that share important features; they may engage in analogical reasoning, which suggests that similar cases reflect a likely similarity in their other aspects as well, such as the resolution of that case (Beauchamp and Childress, 1994). However, pure inductivism suffers when it comes to novel situations. The emergence of new biotechnology or social constructs cannot be efficiently dealt with if one were to choose pure inductive reasoning. This limitation also reveals the inability for inductivism to reflect on our moral tendency to make moral judgments by pre-established guidelines (Beauchamp and Childress, 1994).

Coherentism and its Application

Adapting from John Rawls’s conception of the considered judgments, judgments “in which our moral capacities are most likely to be displayed without distortion”, Tom Beauchamp and James Childress attempt to formulate an ethical framework that combines deductive and inductive moral evaluation to establish a coherent reflective equilibrium (Beauchamp and Childress, 1994). Under this dialectical framework, theory and practice communicate with each other to achieve coherence. The reflective equilibrium lies within the adjusting of considered judgments with pre-established theory and theory with historically-endured practices. Beauchamp and Childress highlight the three following justifications for a good coherent theory (to differentiate from malign yet coherent “Pirates’ Creeds”): resemblance condition, that the moral account resembles the principles that initialized the account (hence, principlism); universalizability, in which the application of judgments remain consistent throughout; endurance, when the coherent theory endures competitive moral accounts and can remain adaptable to concurrent moral challenges. Beacuchamp and Childress state that if coherence can be achieved after repeated testing, then in a similar manner with the process of developing scientific truth, the coherence would be reflecting, or at least approximating the moral truth as well (Beauchamp and Childress, 1994).

Beauchamp and Childress acknowledge the limitations of starting with relatively abstract and general moral principles to obtain concrete and particular moral judgments. They suggest two methods to alleviate this issue: specification and balancing. Specification of principles, as they suggest, not only furthers the coherence within a moral framework by resolving inherent conflicts between principles or rules but also proves helpful in developing real-life policies. Balancing principles, on the other hand, resonates with the Rossian conception of evaluating a certain moral case by its prima facie rightness and wrongness; a prima-facie duty should always be the actual duty unless there is another significant prima facie factor that overrides it, which necessitates balancing in the case of an overriding factor (Pellegrino, 1993). The four prima facie principles that are the most well-known from Beauchamp and Childress include autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. These principles should not be infringed unless there are no other lesser alternatives and the negative effects are minimal when compared to the realistic and reasonable advantages promised in the overriding of the prima facie principles (Pellegrino, 1993; Beauchamp and Childress, 1994).

Criticisms of the Four Principles

In Beauchamp and Childress’s description, the four prima facie principles are equally morally significant. However, this subjects principlism to one of its theoretical difficulties—addressing the issue of conflicting principles. Beauchamp and Childress offer a method of balancing that they believe can help alleviate the issue. Another way of resolving conflicting principles is to construct a lexical ranking of the four principles, or even extracting one supreme principle out of the few (Heinrichs, 2010). For example, arguments have been made that the principle of autonomy should be considered with the highest regards due to its importance in the modern political (especially Western) landscape.

An approach from Robert M. Veatch that recognizes the inherent differences between the “consequence-maximizing principles” (beneficence and nonmaleficence) and the deontological principles (autonomy and justice) proposes considering deontological principles prior to the consequentialist principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence (Heinrichs, 2010). The former two can be traced back to the Hippocratic tradition, while the latter two, with autonomy often coming to conflict with beneficence when it comes to ethical dilemmas such as euthanasia, seems to reflect our contemporary clinical emphasis on informed consent and modern liberalism’s embrace of self-determination (Pellegrino, 1993). This framework, however, still faces the problem of conflicting principles within each category; for example, when autonomy is at odds with justice (Heinrichs, 2010).

Another issue with principlism comes with its claim of common morality. According to Beauchamp and Childress’s description, though ethical theories and their corresponding methods of determining moral judgments often differ, most theories converge on the level of principles (refer back to Diagram 1). This is why these four principles are often referred to as “mid-level principles” (Beauchamp and Childress, 1994). Nonetheless, the social reality of moral multiplicity seems to challenge the concept that there is a common morality based on shared principles that can be agreed upon by all individuals in different cultures. Furthermore, in any given culture, not everyone is given the moral status which treats everyone with the status equally under the common morality (Hodges and Sulmasy, 2013). Beauchamp and Childress address this concern by setting the contents of common morality as first-order while the issues of moral statuses as second-order; they consider the question of moral status to be independent of the coherent structure of the common morality within a given society (Hodges and Sulmasy, 2013).

In this account, however, though one can reasonably concede that the principles of autonomy, beneficence, and nonmaleficence can remain with an independent substantive moral explanation without considering moral statuses, the principle of justice is inherently tied to the distribution of moral status under transcultural settings. To engage in the specification of the principle of justice is to discuss moral status (Hodges and Sulmasy, 2013). Beauchamp and Childress’s principlism thus is left with roughly two ways to rearticulate itself: either through a re-framing of the common morality and the principles within it, such as addressing the issue of justice or to incorporate an account of moral status within the principles itself; or, principlism could concede the claim of common morality’s universality and acknowledge its cultural and political basis and biases; even if there exists an actual common morality, the principlist system in its current iteration would only be an approximation of it at best (Hodges and Sulmasy, 2013).

The Recognition of Differences: Responses to Multiculturalism

Postmodernist Formulation of the Diverse Reality

As an influential philosophical movement during the 20th century, postmodernism challenges the notion of a universalizable conception of truth and/or reality. Though ethical frameworks have always accounted for different moral values, such as principlism’s concession that there can be divergent ethical theories while there remains convergence at mid-level principles, postmodernism calls into question the fundamental idea that there is a common morality, and the practice of imposing one’s moral contents onto another. Against the Kantian conception that there are absolute moral principles, a Hegelian outlook recognizes all of material morality as due to socio-historical contingency (Engelhardt, 2012). Any morality becomes a process and the result of the socio-political state, and any argument of bioethical principles is no longer a result of reason, for reason is universalizable; after the collapse of metaphysical/theological foundations, the essence of bioethical debates becomes a matter of discursive domination and secular bio-politics (Engelhardt, 2012).

While recognizing the difference claim from a descriptive standpoint—that different cultures accept different moral principles and that morality is intrinsically multicultural—postmodernism also aims to deconstruct the argument that morality is itself an objective language. Michel Foucault, a 20th century philosopher known for his analysis of power’s relation with scientific empirical inquiry, coined the term the “clinical gaze” to explain how the modern bioethical perspective of patients as pathological bodies to be inspected by biomedical procedures is not itself absolute or detached from the state that have manufactured and helped facilitating this “gaze” or discourse to begin with (Baker, 1998a). Modern bioethics is deeply entrenched in its socio-political background which sees morality through a particular lens. In the postmodern reading, patients were not inspected under different ethical theories that converge in the mid-level principles, but rather under “gazes” contingent and pluralistic in nature.

Morality and Stories: Narrative Ethics

While the four-principle approach has been criticized by postmodern theory and the multicultural reality, narrative ethics is an ethical framework regarding stories from which we should draw ethical conclusions from. Instead of imagining ethics as an infallible medium from which morally correct judgments could always be made as long as one follows the appropriate set of absolute moral principles, narrative ethics recognizes the fallible nature of moral inquiry; instead of relying on abstract theories to construct our moral reality, stories become the primary focus and the ever-increasing base of knowledge from which ethical theories gain their applicability to reality (Tong, 2002). Ethics also responds to different questions and serves various roles, hence it is more appropriate to use the metaphor of a “toolkit” (in Howard Brody’s term) to describe our ethical processes: we look at dilemmas from different angles using several perspectives and approaches that best fit the situation at hand; only then, can we use our limited yet ever-expanding sets of tools to best resolve questions that does not necessarily have an absolute answer (Brody, 2009).

There are much more in ethics than principles, “rights, virtues, and emotional responses are in some contexts of greater moral importance than principles and rules (Beauchamp and Childress, 1994).” Pure principles cannot elaborate and explain many important clinical values such as gratitude, mercy, compassion, etc. Within the clinical encounter, while a principlist outlook might emphasize a procedural execution of what the medical committee have decided to be “beneficent” or “non-malicious” to the patient, an appeal to narratives would respect listening to the story, the experience, and the encounter from the patient’s point of view (Tong, 2002). While not necessarily contradicting the principlist perspective, narrative ethics necessitates ethical theories to reformulate principles and enhance rational deliberation with narrative illumination. Instead of seeing principles as the end in themselves, narrative ethics recalls the role of the reflective equilibrium as a locus of interaction between abstract theories and “considered judgments”; principles, in this case, are the distillations of the nebulous yet more essential human moral intuitions reflected across our social and historical stories (Arras, 2017).

If multiculturalism implies that one cannot reasonably articulate a framework for common morality that would incorporate everyone’s cultural values, then some argue that narratives which reveal fundamental social beliefs for specific cultures, “foundational stories” such as biblical texts and epic tales, could be the new groundwork for ethical deliberation (Arras, 2017). Abandoning universality for socio-historical contingency, these ever-evolving stories offer clear, necessary and sufficient conditions that form an action-guiding ethical framework; while Kantianism can reveal what one should not do, as we should not go against the categorical imperative, stories are specific and reveal what one shall do in that scenario, such as being a Good Samaritan (Arras, 2017).

This outlook, however, raises new questions. Though narratives and moral values are essential in providing useful descriptive dimensions to an otherwise purely principlist perspective, as Beauchamp and Childress have remarked above, an ethical system cannot depend solely on these “foundational stories” either. This approach assumes an overly ideal conception of the relationship between narratives and societies. Stories, like principles, do conflict and face moral disagreements not only on a transcultural level, but within a culture as well. By substituting principles with stories, one would find themselves facing again the problems principles face: which narratives should guide one’s action if several narratives within a culture can all arrive at different answers (Arras, 2017)? Stories can also be biased or deceptive, and an overly relativistic standpoint that embraces every perspective can deprive bioethics the ability to create moral judgments; in the process of celebrating people’s differences it is crucial not to overlook the larger social tapestry wherein these different communities interconnect (Arras, 2017). Ethics is more than stories.

Baker’s Contractarianism: Maintaining Normativity under Descriptive Multiplicity

Ethics, in its core, should be capable of offering transcultural moral judgments. Principlism and moral fundamentalism, which believes that there are universally accepted principles, can be undermined by the empirical difference claim; radical relativism, however, would also prevent us from condemning problematic practices. For example, during the Nuremberg Trials, when Allies had to prosecute Nazi doctors and scientists, it was important to derive an absolute moral framework that neither offends the difference claim nor condones the actions of the Nazi scientists (Baker, 1998a). While neither principlism nor relativism can offer such a moral formulation, Robert Baker suggests that a model of contractarianism may offer useful insights.

Principlism’s assumption that there is mid-level convergence is problematic for cases such as rebel societies which deliberately define themselves as anti- (traditional Western) principles. Also, an established principle in one culture may be articulated in ways that may not be compatible with another culture’s way of conceptualization (Baker, 1998a). Thus, a firm grounding for an ethical framework that is able to justify transcultural judgments without dismissing the empirical fact of multiculturalism should be found outside of ethical theory by engaging in “level 5 metaethical analysis (Baker, 1998a).”

The central concept of contractarianism comes from giving normative strength to the idea of contracts. Moral norms and the authority that promote those norms gain their legitimacy from the fact that people accept and agree to obey them (Baker, 1998b). This sense of “acceptance” should not be a kind of postulated acceptance, which would imply in the case of the Nuremberg Trials that the Nazi scientists were wrong for the reason that they disobeyed principles of which they were ignorant and were prescribed by those who placed them on trial. By their own socio-philosophical model of ubermensch and untermensch, the principles they were accused of violating were not intuitive in the Nazi ideology (Baker, 1998a), and it is evident that many Nazi scientists at the time considered themselves to be doing what is morally right. Instead, “acceptance” should indicate a rational agent’s self-willingness to bind themselves with the moral norms and authority; norms are illegitimate when no rational agent would ever, in any circumstance, accept to be bound by them (Baker, 1998b). The Nazi human experiments would be, therefore, meta-ethically illegitimate since regardless of ethical theories, the human subjects would have never actively consented to be an untermensch under the Nazi regime (Baker, 1998b). The Nazi scientists have violated the non-negotiable and primary human rights of their subjects. Though one can formulate primary goods differently across cultures, what they consider to be primary should never be transgressed. Nazi scientists can be condemned under this framework not because of one universal moral principle, but their reluctance to play by the games of moral agreement and their dismissal of the primary goods their subjects hold (Baker, 1998b).

The concept of negotiated moral agreement, however, needs to address certain theoretical difficulties to be a practical moral framework. Realistic agents do not necessarily have the same amount of power and ability to negotiate, and when there are situations of oppression where one’s voice can overshadow another’s articulation for moral values and can make non-negotiable the imposed moral rules, contractarianism becomes an incomplete method of moral justification (Beck, 2015). The emphasis on “acceptance” also pre-supposes the importance of the principle of autonomy, hence contractarianism is not completely detached from engaging in the discussions of ethics-leveled principles (Beck, 2015).

Phenomenology

Theory of Phenomenology

Phenomenology is a philosophical tradition from the 20th century, with its emergence mainly attributed to philosopher Edmund Husserl, which attempts to provide an ontological account of essence and human existence through reflections of human perception and consciousness. An important maneuver in phenomenology is epoché, where the utilization of it, whether eidetic or phenomenological, results in the uncovering of essence, eidos, of different objects and experiences (Pellegrino, 2004). The reductive process of epoché is practiced through suspending the natural attitude, or the attitude of our common sense that we take for granted, and through reflecting and “bracketing” our structure of perception, phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty remarked that a pre-given life-world will be revealed (Rashed, 2015). The life-world is the basis and the horizon of meaning.

Phenomenology rejects the naturalist account of the body that is prevalent in modern biomedicine, which sees the body as something that is detached from the patient’s subjectivity, the Cartesian res extensa from the pure consciousness (Goldenberg, 2010). Phenomenology argues that we are embodied, that our structure of consciousness is fundamentally inseparable from our body’s material interactions; we don’t perceive organs within us as tools that our transcendental mind uses to achieve a purpose, rather, the immanent thought functions along with our flesh, our actions being an immediacy of our consciousness. We rarely think about moving our hands, we simply move our hands, our intentionality of action intertwined with the action itself (Svenaeus, 2010).

Therefore, phenomenology rejects the notion that suffering is merely a physiological phenomenon. A body in pain alters the sense of being of the person, for consciousness is embodied, and the suffering results in the person’s feeling not-being-at-home (Svenaeus, 2014). More than inflicting sensory pain, suffering alienates a person by forcing them to perceive the world through completely different lens; suffering is a mood, it is not simply a change in a factual sense, it fundamentally disturbs a person’s way of understanding the surrounding world (Svenaeus, 2014). For example, if I am a person who experienced a major injury that results in my reliance on a wheelchair as the medium for mobility, what changes is not simply that I am now in a wheelchair when I once wasn’t. The world, in fact, would appear differently to me, for even though a difficult ramp by a stair has never changed its material nature, it presents itself to me, phenomenologically, now as an obstacle. Meaning behind a certain event, and in this case illness, lies not only in the biological nature of the happening, but also in how the event appears to the subject affected.

Ethical Implications of the Phenomenological Perspective

Phenomenology, similar to Narrative Ethics, emphasizes the stories and experiences that patients and/or agents of the cases tell. The stories and subjective perspectives allow better judgment and are, in fact, what allow us to understand principles in that case (Greenfield and Jensen, 2010). Phenomenologists are thus particularists when it comes to the actual duties, for they consider cases in a holistic standpoint without referring to principles that hold any substantive moral valences on their own. The usage of hermeneutical phenomenology, for example, not only analyzes the lived experiences and the meanings of these phenomena from a first person/second person perspective, but also elaborates the concepts used in different ways by the researchers and subjects of the case at hand (Zeiler and De Boer, 2020).

Consider the following clinical encounter described by Richard Zaner: a female patient was informed that given the medical evidence up to this point that her baby be aborted lest the baby be induced before full term and would thereby suffer congenital anomalies that would require great clinical care after birth (Zaner, 1994). The case met an impasse when there emerged conflicts between the concerns of the patient and her husband with the clinician who suggested the abortion. From Zaner’s communication with both the patient and the clinician, he explained that the conflict emerged because of a fundamental phenomenological difference between how the results and deciding factors which proposed the baby to be aborted appear to the two agents in this encounter. The clinician, educated in the medical field that considers life from a positivist and naturalistic standpoint, receives the information that the baby is at “high risk” to be sufficient argument for considering abortion for the patient. The patient, being the direct subject that must go through complicated moral considerations, finds the clinician’s response cold and disturbingly indeterminate (Zaner, 1994). Either side is unable to understand why the other cannot see things from their perspective. The statistical likelihood of postnatal disease, in this case, the seemingly objective numerical information that decides abortion has, in fact, two meanings by virtue of two different beholders. It is important, then, to resolve this case utilizing a phenomenological lens, and to see these meanings as both subjectively and intersubjectively construed.

Through using epoché to reflect upon the intersection of the patient-clinician life-world, the essence of the clinical encounter can be revealed; phenomenological ethics hopes to ground ethical theory internally by reflecting on the nature of medicine and treatment (Pellegrino, 2004). By engaging in the method of reflecting on the subjectivity of the patient, ethics can achieve a sense of reflexivity that unveils the meaning of the phenomenon, be it illness or an ethical dilemmas, to account for the lack of consideration in the naturalist perspective of the social milieu and the agency of words from people who express them (Murray and Holmes, 2013). Phenomenology is a way to inspect cases that reveals the meaning of the elements within the case and our ethical reflections regarding the case.

Concluding Remarks

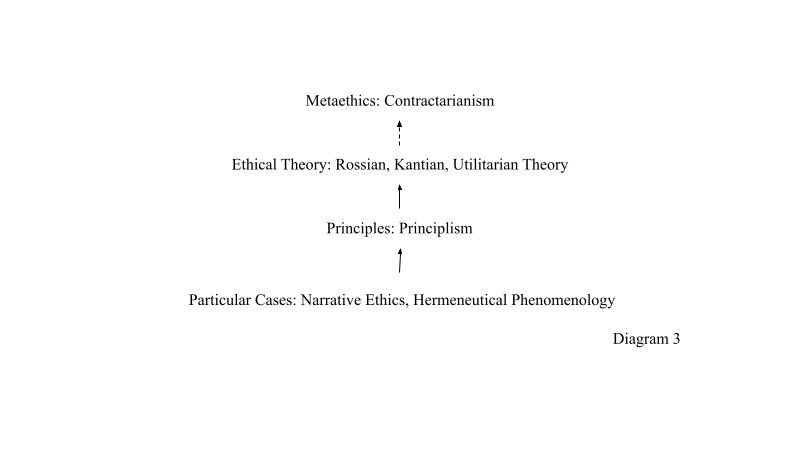

The approximate structure of the different theories can be concluded by the following diagram:

The Rossian conception of a universal absolute actual duty, along with the Kantian categorical imperative and the Utilitarian evaluation based on maximizing utility, locates a convergence on the level of ethical theory. These three frameworks agree with the existence of an absolute moral principle that is applied to evaluate different cases. Principlism, agreeing with the idea of the reflective equilibrium from Rawls, develops a moral framework that is based on a dialectical process between the ethical theories and particular judgments. To avoid infinite regress, Beauchamp and Childress initialize the ethical reflection with “prima facie” considered judgments that they find to be archetypal of a common morality. Principlism argues that its ability to create moral judgments stem from the potent convergence of principles and its method of either specifying or balancing these principles. Principlism concedes that although the contextual appearances of different principles may differ across cultures, the nature of these principles does not change. The difference claim, however, undermines the claim of common morality. In the presence of empirical cultural-moral difference, contractarianism establishes moral judgments by virtue of meta-ethics. By viewing different ethical frameworks as different contracts, the invalidity of any action stems from its violation of the contractual structure, such as when one imposes circumstances upon an agent when no rational agent would have actively subjected themselves to the said circumstances. Instead of finding moral establishment from principles and above, narrative ethics and hermeneutical phenomenology establishes justifications on a case by case basis. By illuminating the case from either the stories they tell or the deeper social milieu that shapes a person’s life-world, ethics can better reflect upon its role and position when it comes to individual cases.

This is by no means an absolute diagram. Every theory, apart from its central locus of convergence, reflects upon other theories when it comes to the other levels. Theories, therefore, are not mutually exclusive. A phenomenological perspective can coexist with a common morality based on principles that were established through a phenomenological epoché that reveals a commonality shared by all human-beings’ existence. Principlism requires specification and balancing that calls for particular contextual analysis. While each theory suffers from its theoretical limitations, it may be that an appropriate ethical framework will emerge from a synthesis of the different theories, or a new theoretical construction that both addresses empirical differences and has a strong normative power. Either way, the challenge of ethics is to always reflect upon its nature and the judgments that are created by the assumptions of the corresponding moral framework. It is because of this that the discourse on bioethical frameworks is likely to continue for a long time.

Works Cited

Arras, J.D. (2017) Nice Story, but So What?: Narrative and Justification in Ethics. In: Childress, J. and Adams, M. (eds.) Methods in Bioethics. Oxford University Press.

Atwell, J. (1978) Ross and Prima Facie Duties. Ethics, 88(3), pp. 240–249.

Baker, R. (1998a) A theory of international bioethics: multiculturalism, postmodernism, and the bankruptcy of fundamentalism. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 8(3), pp. 201–231.

Baker, R. (1998b) A Theory of International Bioethics: The Negotiable and the Non-Negotiable. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 8(3), pp. 233–273.

Beauchamp, T.L. and Childress, J.F. (1994) Morality and Moral Justification. In: Principles of biomedical ethics. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–43.

Beck, D. (2015) Between Relativism and Imperialism: Navigating Moral Diversity in Cross-Cultural Bioethics. Developing World Bioethics, 15(3), pp. 162–171.

Brody, H. (2009) Illuminating a Case: Alternative Ethical Approaches. Humanism and the Healing Arts, May (2009), pp. 6–13.

Dabbagh, S. (2008) In Defense of Four Principles Approach in Medical Ethics. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 37(Supple 1), pp. 31–38.

Engelhardt, H.T. (2012) Bioethics critically reconsidered: Living after foundations. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, 33(1), pp. 97–105.

Goldenberg, M.J. (2010) Clinical evidence and the absent body in medical phenomenology: On the need for a new phenomenology of medicine. International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, 3(1), pp. 43–71.

Greenfield, B.H. and Jensen, G.M. (2010) Understanding the Lived Experiences of Patients: Application of a Phenomenological Approach to Ethics. Physical Therapy, 90(8), pp. 1185–1197.

Heinrichs, B. (2010) Single-Principle Versus Multi-Principles Approaches in Bioethics. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 27(1), pp. 72–83.

Hodges, K.E. and Sulmasy, D.P. (2013) Moral Status, Justice, and the Common Morality: Challenges for the Principlist Account of Moral Change. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 23(3), pp. 275–296.

Murray, S.J. and Holmes, D. (2013) Toward a critical ethical reflexivity: phenomenology and language in Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Bioethics, 27(6), pp. 341–347.

Olsen, K. (2014) Ross and the particularism/generalism divide. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 44(1), pp. 56–75.

Pellegrino, E.D. (2004) Philosophy of Medicine and Medical Ethics: A Phenomenological Perspective. In: Khushf, G. (ed.) Handbook of Bioethics: Taking Stock of the Field from a Philosophical Perspective. Philosophy and Medicine. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 183–202.

Pellegrino, E.D. (1993) The Metamorphosis of Medical Ethics: A 30-Year Retrospective. JAMA, 269(9), pp. 1158–1162.

Rashed, M.A. (2015) A critical perspective on second-order empathy in understanding psychopathology: phenomenology and ethics. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, 36(2), pp. 97–116.

Svenaeus, F. (2014) The phenomenology of suffering in medicine and bioethics. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, 35(6), pp. 407–420.

Svenaeus, F. (2010) What is an organ? Heidegger and the phenomenology of organ transplantation. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, 31(3), pp. 179–196.

Tong, R. (2002) Teaching bioethics in the new millennium: holding theories accountable to actual practices and real people. The Journal of medicine and philosophy, 27(4), pp. 417–432.

Zaner, R.M. (1994) Experience and Moral Life: A Phenomenological Approach to Bioethics. In: DuBose, E.R., Hamel, R.P. and O’Connell, L.J. (eds.) A Matter of Principles?: Ferment in U.S. Bioethics. Trinity Press International, pp. 211–239.

Zeiler, K. and De Boer, M. (2020) The Empirical and the Philosophical in Empirical Bioethics: Time for a Conceptual Turn. AJOB empirical bioethics, 11(1), pp. 11–13.